by Val Cubitt, daughter of a FEPOW

The Monkey on His Back - A True Story of Captivity with the Japanese in WWII

In Memory of My Dad

by Val Cubitt

My dad was taken prisoner at the fall of Singapore 1942. As children, to make us laugh, he often told this story.

“When I was a prisoner of the Japanese, I had been very poorly, in the camp hospital in fact. As I recovered, I was put on ‘light sick duties’, this meant sweeping all the leaves from the Japanese Officers’ camp. Of course in Singapore, the leaves were always falling, there were no seasons. The officers had a pet monkey, on a very long chain, and every time it caught sight of me, thin and weak, endlessly sweeping leaves, it would run down from its tree, jump on my shoulders, and tug and pull and yank at my hair, chattering away! Of course, the Japanese officers loved this, and called to others to watch. They clapped, they jeered, they laughed, they thought it was hilarious, and, of course, I had to keep sweeping, I daren’t do anything to the monkey, on pain of severe punishment. Until one day...

I was sweeping, the guards weren’t around, and the monkey came. I looked around, it was all clear, I reached up, I lifted the monkey down, and I gave it a real good hiding! The next day, there I was, there the guards were, and there was the monkey in his tree, chattering and watching! The guards waited expectantly, they nudged each other, they grinned, waiting for their free amusement, but the monkey never jumped on my shoulder again!”

Our dad, through his terrible memories of captivity, carried that monkey on his shoulders, for... almost all of his life. This is his story.

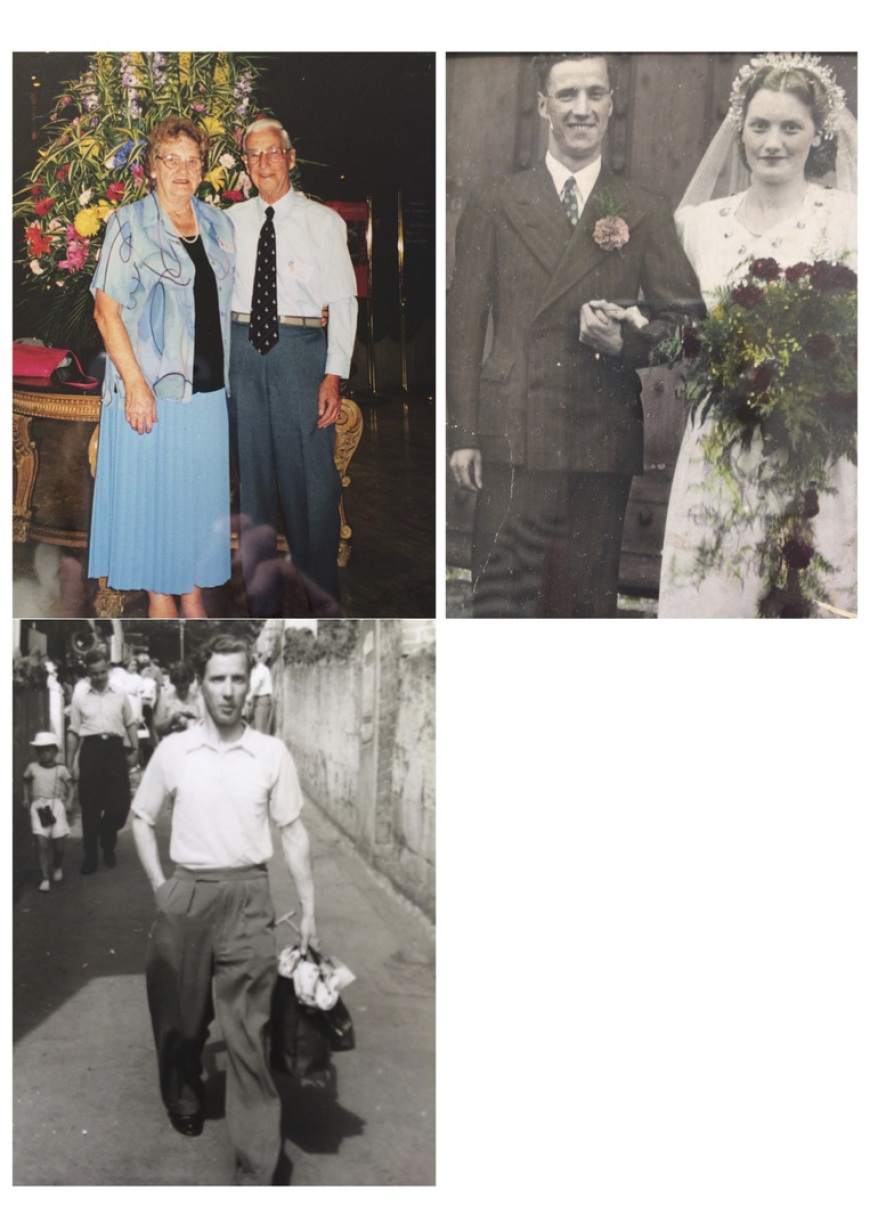

He was 21 on 3 October 1939, when war broke out. He was called up immediately, enlisted into the Royal Artillery and did his basic training in Norfolk, Scotland and Monmouth. A peace-loving young man, not long out of his teens, was now a soldier in the 148 Field Regiment of The Bedfordshire Yeomanry. He was allowed a final leave before his overseas posting, which was to support Montgomery’s 8th army in the desert. His training was for desert warfare. He set off from Liverpool in the dead of night in October 1941, with the 18th Division, combat uniforms and equipment all painted in desert camouflage. At that time the U boat campaign was at its height, and at church parade on board ship, they sang ‘For those in peril on the sea...’ with extra enthusiasm! But fate intervened, and while at sea, Pearl Harbour was bombed. Dad’s division was immediately ordered to divert to Singapore, the equipment had to be re-painted green, for the jungle, and they were ordered to prepare for a fighting landing!

Two weeks of bombardment followed, with no air or sea backup. Singapore fell, and on 15th February 1942, my dad was a prisoner of war...he was 23 years old. It was the beginning of three and a half years of starvation, slave labour, deprivation and disease. The first year in Singapore was bad, but worse was to come. The Japanese said they had rest camps in Burma and Thailand (Siam as it was then), and they would be moving prisoners. My dad was put into F-Force which suffered the most casualties of all. They travelled for 5 days and nights packed into steel-sided railway carriages, 35 to a carriage. It was impossible to either sit or lie down at the same time. The sides were so hot they couldn’t be touched and men had dysentery. Some never made the end of that journey. Those who did were then forced to make the rest of the journey on foot, from Banpong to the furthermost reaches of the railway. It came to be known as The Death March. They set off through jungle in the monsoon period, throwing away kit as they went, as it became impossible to carry. Many did not make it...my dad did. Kuwii, became his work camp, a filthy clearing near the railway, already inhabited by despairing Dutch prisoners. Here they were to set to work building rattan huts to live in, before the nightmare began.

But the human spirit always warms the heart! In later life, when dad needed to talk about it; he shared some special moments with us. He told us how once, when lying in a sick hut, a voice from the bamboo slats next to him, asked him his name, when he answered ‘Ron’, the voice said, ‘Ron, will you hold my hand?’ They held hands all night. In the morning the fellow prisoner had lost his fight for life, but dad had given all he had to give...a little comfort. And then, when my dad was close to death from starvation and disease at 24, with no will left to live, one of his own officers was passing through his camp, trying to keep records of prisoners. He recognised my dad, dragged him out of the sick tent, ordered him to sit on an upturned log and began shouting at him, ‘ What are you doing, lying there, think about your mum. What would she say if she saw you like this?’ ....He then collected dad’s rice ration and forced him to eat, returning every day, until finally, dad’s spirit came back, and he recovered enough to join the working parties again, building embankments. This continued day after day, day after day...until the railway was completed.

Out of the 55 in my dad’s camp, which had also been hit by cholera, 8 crawled out. Dad was one of them. They were transported back down the river by barge calling in at Chungkai. Then dad recognised an officer and called out to him. Dad weighed just over 4 stones, was ragged, bearded and dirty. The officer didn’t recognise him, until he heard his voice. ‘Its Ron!’ The officer immediately called for some rations and help. He tried in vain to persuade the Japanese to let dad stay for just a few more days, but to no avail. Just as they were ordered back onto the barge, he gave dad all he had, 2 ticals (coins), a few vitamin pills and a small tin of insect itching powder. Dad never knew whether it was the things he was given, or simply the kindness and belief he received that helped save his life. But he truly believed that it was gestures like this that helped him and others survive, when at their lowest.

My dad arrived back in Singapore at night. He was taken to the Changi area and spent time in Changi jail itself. He spent the rest of the war there, with little food and endless work, but compared with life on the railway, it was home.

As the end of the war came, he had survived. It was close. The prisoners were actually digging trenches for their own graves, when the second atom bomb was dropped. If it hadn’t been, thousands and thousands more would have died...on both sides.

Our dad was the most loving dad anyone could have wished for, always full of fun, and song, with holidays and happy times in abundance. He was never a materialistic man...life itself was too precious. Yet, we knew the scars, the memories and the nightmares never left him, until perhaps, the encounter with a Japanese Christian lady in the 1990s named Keiko Holmes.

Keiko had made reconciliation for FEPOWS (Far East Prisoners of War) her mission. She began attending FEPOW meetings, arriving the first time, at the Barbican Centre. This did not go down well, and she was asked to leave, but still she persevered and continued to turn up. She tried to talk to them. They refused. She tried to encourage them to go on a pilgrimage to Japan with her. They refused. She asked them to talk about their experiences. She listened. And then gradually, something began to happen. These old men began to think. For years my dad refused to be drawn in, preferring to keep the hate and hurt and torment hidden away. But one day he did talk to her. When she asked if she could tape what he said, he agreed. Slowly, trust and friendship grew. Dad never wanted to go to Japan, he didn’t want to meet another Japanese person, but by now, at almost 80 years old, he wanted the pain and hate to go away. I remember him looking at his two grandchildren, our children, Laura and Jim, and saying, “You know, I would hate anyone to blame my grandchildren for something I did, perhaps I need to stop hating theirs.” And with this thought firmly in his mind, he agreed to go on the pilgrimage, but only on condition that he could talk in schools and colleges and meetings about his experiences. Good needed to come from such a difficult journey.

He did go, with mum. He did tell his story – he also visited a Japanese family in their home, and heard how they had lost relatives in Hiroshima. He met their grandson, Yuji, 18 years of age, the same as Laura at the time.

He also met a guard from F-Force. This was unexpected and utterly and totally one of the most difficult moments in my dad’s life. He wanted to hate him. He wanted to lay at his feet, the deaths and needless suffering of so many young men, friends and comrades. He wanted to...But all he saw, was an old man, who like my dad was scarred. He saw a man full of remorse for the part he had played. We have a photograph of that encounter, and the only words my dad could say to him was, “I think it is time for you to get on with your life, and I will get on with mine.”

But did this heal the scars for dad, you are probably wondering, did he find reconciliation and peace? When it was time to leave, mum and dad were standing at the railway station, next to another railway track that would begin their journey home. Yuji and his family were there to wave them off. Yuji stepped forward, looked into my dad’s eyes and said, “Ron, I am so sorry.” My dad, with eyes full, looked back into his, and said, “But, Yuji, you have nothing to be sorry for.” Yuji replied, “I am saying it for my people”. In that moment, my dad said he felt a huge weight lifted...the monkey on his shoulders had gone. That one apology, from a boy, standing next to a railway line in Japan, had wiped away the hate. It was a moment that as a family, we treasure, and will never forget. A moment we remember with thanksgiving... Yuji, you will never know the weight of those few words. It took one young man to do what a nation had not. It really is individuals touching the hearts of other individuals that can change the world!

A year later, Yuji came to university in England. He stayed with my mum and dad for a week. They brought him to visit Stratford and he went to the Theatre with our daughter Laura. We had a lovely time together. Dad said, he would sometimes find himself quietly looking across at Yuji as he sat chatting in their sitting room, and think to himself, “Well I never, how life goes full circle.” And my mum cooked a rice pudding for him, ‘to make him feel at home’! I’m not sure Yuji enjoyed his rice with milk and sugar!

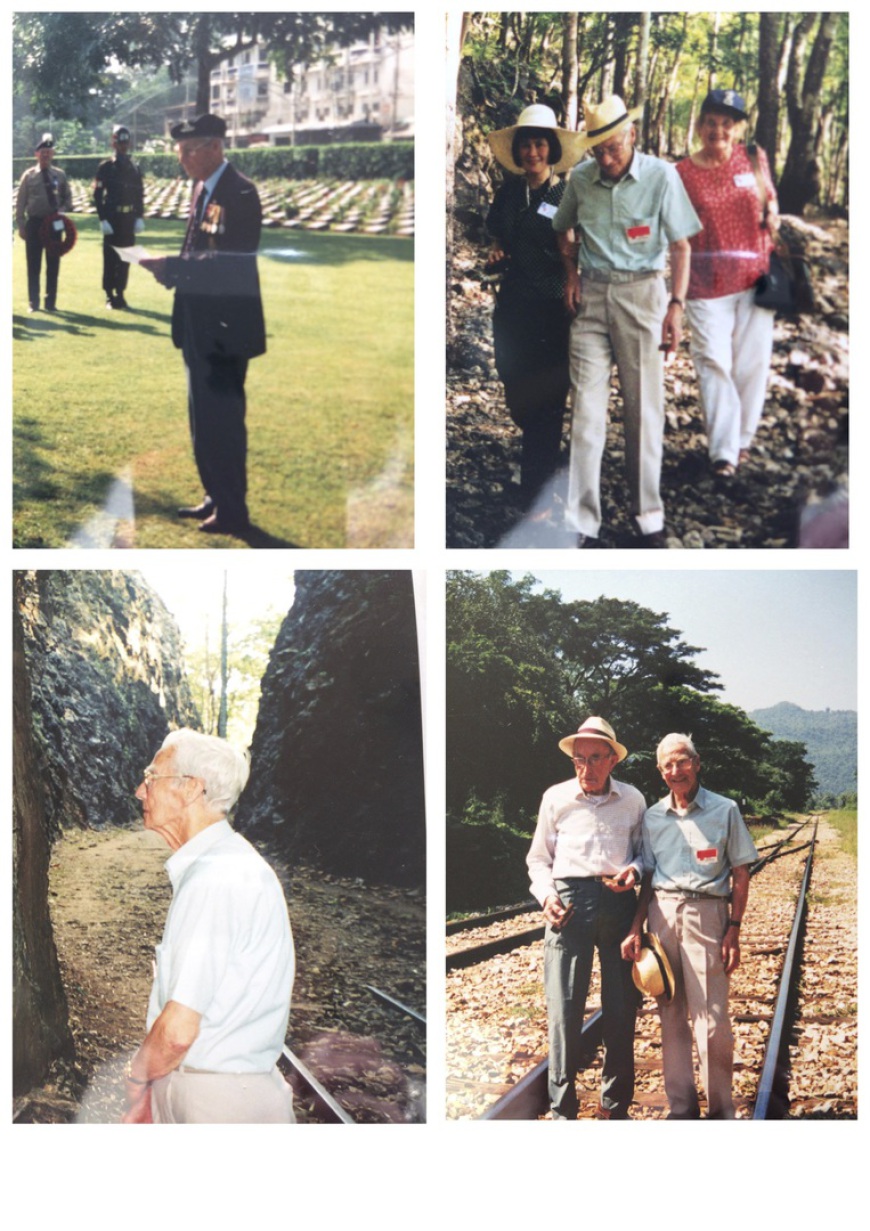

The following year, my dad’s 80th, we all went with him on a pilgrimage to Thailand. We visited the infamous Burma/Siam railway, the bridge over the River Kwai, and the memorial services at Kanchanaburi and Chungkai, where we found the graves of friends, some of whom dad had helped to bury in those railway camps. It was deeply moving! We then spent some time in Singapore and saw Changi Jail. I wrote the poem below, which Pete read at dad’s funeral in 2001.

We still keep in touch with Keiko, and she continues to work for AGAPE (later renamed ‘Agape World’) and reconciliation. She was awarded the OBE and mum and dad and their whole pilgrimage group were invited to attend the ceremony at Windsor Castle. We receive all her newsletters. She now organises visits for the grandchildren of FEPOWs, and both Laura and Jim went on one such pilgrimage and stayed with Japanese families. Mum is invited to a reunion at the Japanese Embassy every year.

When dad died in 2001, aged 82, there were many mourners, family, friends, FEPOWs....And flowers from a Japanese family, with the words, “For Ron’s Grave”.

The scars were healed, the hate had gone, the monkey no longer on his shoulders, the circle was complete.

The Traveller by Val Cubitt March 2000

A lone train clattered northwards,

Through jungle, now cleared, and then,

Past mountains, rivers and valleys

To a clearing once filled with men.

And a traveller stood and wondered,

Waving a thoughtful hand, head high,

As the train weaved its way ever onward,

Towards a clear, blue Thailand sky.

He gazed with wonder around him,

Old sleepers, their work long spent,

Strewn among the green, gentle grasses,

Where shadows of friends came and went.

He bent down, and picked up gently,

A rusty nail or two,

He held them with a father’s tenderness,

As distant memories drifted through

The traveller walked through a field of green,

Surrounded by headstones bold,

Each one, a name, a life etched out

In letters of burning gold.

They lay in rows, not tattered and torn.

They lay, no longer alone,

But forever a part of this eastern land,

Which had become their home.

The traveller looked, his blue eyes

full of tears and love for each one,

As his gaze turned and confronted,

The land of the rising sun.

There was no anger nor hate in the silence,

Only peace and love for the dead,

“I came back”, he whispered,

And they answered.

“I kept my word,” he said.